EQ Basics

There are various factors which determine an EQ’s sound, the shape of the curve, various saturation characteristics, time domain shifts and more. In this article we’ll be looking at all these factors and their importance when considering an EQ. Then I’ll look at some of my favourite software EQs and why I think they stand out from the crowd.

The first thing to consider is the shape of the EQ curve which. If you are not familiar with the basics of EQ curves this article https://www.izotope.com/en/blog/mixing/principles-of-equalization.html gives a good overview.

As we all know EQ has two primary uses, to boost certain frequencies and to cut certain frequencies. The type of curve the EQ has is likely to be very different depending on whether it’s used to boost or cut. When you boost, as a rule of thumb, the smaller or tighter the the Q (the width of the bell) the less transparent the EQ will be. However smaller Qs also give you more precision in the frequencies you boost. You can boost a small range of frequencies, like the attack of a kick drum, without affecting other nearby frequencies which you don’t want to boost. Used carefully tight Qs are an essential mixing tool. But without care, they can easily make things sound over processed and unnatural. A wider Q on the other hand will sound more transparent and therefore more natural. However you won’t have the ability to be very specific about the frequencies you boost. It’s all a matter of which tool you need for the particular job at hand. When used for cutting, the width of the bell takes on a completely different character. Using a small Q to cut, you can often very transparently remove a problem frequency. So it has almost the opposite effect of boosting with a small Q.

However there is an awful lot more to bell shapes than simply the width of the Q and these differences can have a profound effect on the sound of the EQ. Consider the following EQ shapes:

Mid Q boost. A good shape for general EQ work as it has a balance between precision and transparency.

Narrow Q boost. More precise but also more resonant, meaning potentially less transparent.

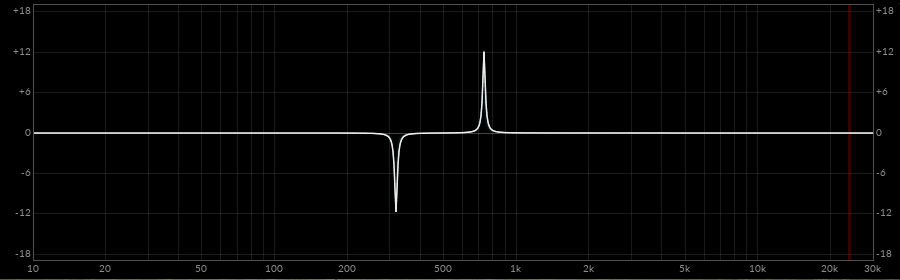

Ultra narrow Q cut and boost. An ultra narrow Q can be useful for surgical cuts, but will be far too resonant to use as a boost unless you’re after special effects.

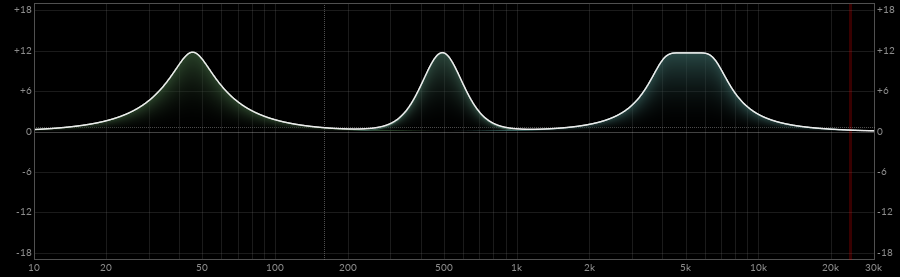

Three bands with similar Q width but different bell shapes. Note that with the first two curves, although the top of the bell is a similar width, the shape of the sides of the slopes are very different. The third curve has similar shaped sides to the first, but the top of the bell is very different from either of the other two. Each of these bell shapes impart a different character to the sound.

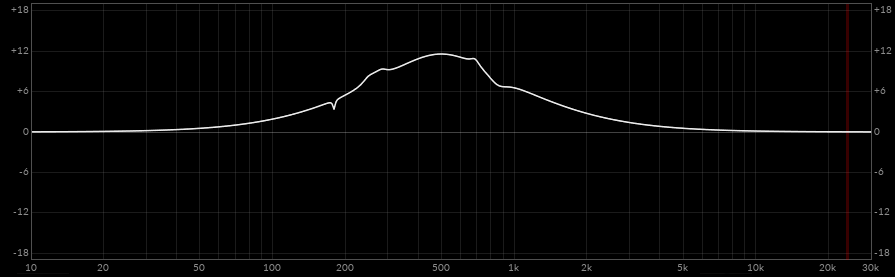

Pultec style EQ curve, where two closely overlapping bands are moved in opposite directions.

Complex bell shape. Some analog EQs will have complex shapes due to idiosyncrasies in the circuits. This can affect the character of the EQ.

What is interesting about the complex shape is that in circuits that produce these, the shape itself will very likely change depending on the amount of boost or cut, the frequency it’s set at, the Q and may even vary depending on the level of the signal going into it. So there’s a lot of complexity there.

So potentially you can have a complex curve that is changing subtly as the incoming signal coming changes. At the same time you could have a complex set of added harmonic saturation being imparted by the circuit which also changes depending on the input level and frequency. You can imagine that at this point the EQ can potentially be something akin to a living breathing entity. Done well this can sound fantastic, which is why the best hardware is so revered. But it’s a very fine balance, get it slightly wrong with a hardware pice which is not well maintained, or one which was not brilliantly designed, you end up with something that simply makes a mess of the sound.

In the software world, as long as you are using plugins from a good manufacturer, you avoid the potential hardware has of muddying the sound. If the plugin is an emulation from a high end manufacturer, then they will have emulated a great hardware piece which was in prime condition, or revered for some unique characteristic. Noise and unwanted distortion can be removed, added to taste, or even increased beyond what the hardware could produce. Alternatively some audio software designers have used component modelling to idealise the hardware or used extended modelling techniques take the plugin to places beyond the capabilities of hardware. For example, you can vary the kind of saturation that is produced by an EQ independently of the EQ type. So you could use an EQ shape form one piece of hardware and add the saturation from a different piece of hardware. Or have a range of different saturations that rather than being modelled after particular hardware are chosen purely for their subjective musical qualities. These can be added to which ever EQ curve you choose. There are many incredibly useful variations on these ideas available in software.

There are also an increasing number of plugins which add signal dependent saturation. In other words the amount and character of the saturation changes depending on the level and frequency content of the audio going through it. This is exactly what happens in hardware and why great hardware sounds the way it does. The great thing from my point of view is that in the plugin world there is enormous potential to take these sound enhancing properties well beyond the reach of any hardware. This is already beginning to happen with some of the more forward looking developers.

Waves H-EQ offers independent control over EQ curve, saturation, and noise based on a variety of modelled hardware EQs as well as some unique digital EQ curves

As if all this wasn’t enough, there is actually a lot more to EQ than just shape, saturation and non-linearity/signal dependancy. There is the whole area of the time domain. All EQ causes time domain distortion. This is not necessarily a bad thing at all. It can in fact be a very good thing. This is not distortion as in fuzz or sound break up. It’s not the same thing as saturation or harmonic distortion. Distortion is a broad term. Any change at all from the original signal could be classified as distortion. By the same token you could say that in a live venue the effect of the air on the sound as it travels over distance, and the reverberation and vibration of various surfaces in the venue, are all types of distortion, as these things all change the sound’s frequency, dynamic, transient properties. and more. It’s more a matter of whether a change to the sound, distortion if you will, is pleasing to the ear or not. Does it enhance the music or take away from it?

With this in mind, it might be better to think of these time domain distortions more as different tonal qualities imparted to the audio by the EQ. Transients can be smeared in a very pleasing way or in a not so pleasing way. This doesn’t just affect the momentary attack of a sound, it can effect a much wider portion of the sound. Analog EQs or emulated analog EQs are often characterised by specific time domain distortions. But purely digital EQs also distort in the time domain, all EQs do. So it’s a matter of, how much distortion and whether its a distortion which enhances the sound or takes away from it. The more extremely you boost EQ, the steepness and shape of the EQ curve all affect time domain distortions, whether it’s analog or purely digital EQ.

Linear phase EQ, which can only exist in the digital world, is compltely free of one kind of distortion known as phase distortion. For this reason it can be very useful in various mixing and mastering situations. However, Linear phase EQ has the potential to cause significant time domain distortion in the form of pre-ringing. Pre-ringing in certain situations can for example, destroy the transient of a drum hit. So linear phase EQs are not a magic bullet, they need to be used with care, but are an essential tool for certain tasks.

So with all the EQs out there, which do I personally use the most and recommend? Here’s my list with some comments about why I like each of these EQs.

Transparrent EQs

Eiosis Air EQ. I really like the clean transparent sound of this EQ, and is along with the FabFilter Pro-Q3, my go-to work horse EQ for many tasks. It is also one of the most versatile and precise EQs on the market. All the bell shapes shown in this article were made in seconds using the Eiosis EQ. Though less important than the other features, I find the unique visual display of the curves the best on the market as it calibrated to the human ear rather than being linear, which makes it incredibly intuitive to use.

FabFilter Pro-Q3 is another great sounding and ultra versatile clean, transparent and precise EQ. I find myself using this as often as the Eiosis EQ for precision work. It has some innovative features and works as a dynamic EQ as well.

Character EQs

Now on to the EQs which by design are not as transparent or as precise, but which impart some special sonic qualities to the sound. This is where, time domain smearing, saturation and complex curves really come into their own. Here’s a typical example of how these kinds of not so transparent EQs can be essential tools. A world class, beautifully maintained grand piano is not something you often find the sorts of small studios jazz musicians can afford to record in. So it’s very common to have a piano which though well tuned, is sounding pretty lack lustre. Often what these pianos, typical of smaller studios, have are worn hammer pads and old strings. This results in a lack of upper mid tone and the ability to project well on a recording, especially in a dense arrangement. In short the piano sounds a bit dull and lifeless even if the player is world class. What it really needs is a boost in the upper mids to help it project and sound more like it would if the hammers and strings were well maintained. However, typically in this situation if I boost the upper mids with a clean EQ you just don’t get the effect I’m after. Though it boosts the intended frequencies, because it’s so clean it also bring out details in the tone which are the result of a worn instrument. In short, there’s a thinness and spikiness to the sound due to the old felt and slightly dead strings. Where as the same boost with Acustica-Audio Azure or Magenta will smear those boosted frequencies in a very nice sounding way, resulting in a thicker sweeter sounding upper mids on the hammer attack. The result is a lot closer to the sound of a well maintained piano than you ever get form a clean EQ.

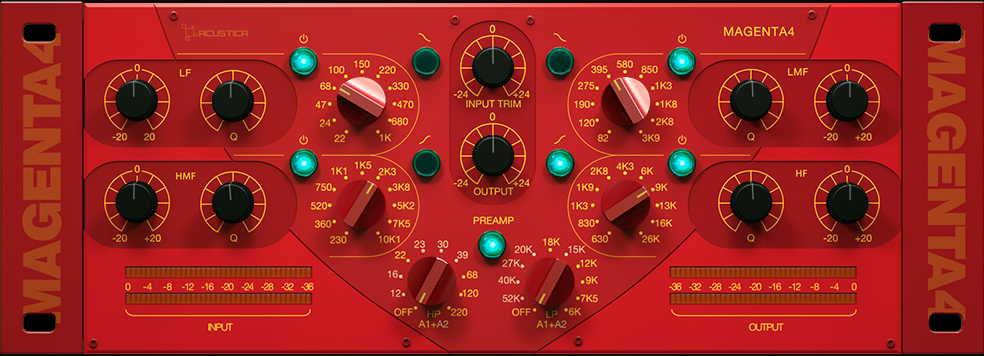

Acustica-Audio Magenta. This EQ based on a famous hardware unit, is a long way from precise or transparent. However it can add weight to the low end, smoothness to the mids, and a sheen to the top end that a clean EQ simply can’t achieve.

Slate Digital FGN Neve EQ emulation. This is a dirty and aggressive EQ, but it can bring out the breathiness of a vocal or the presence of a snare in a way no other EQ can.

Waves Scheps 73 same as above.

Acustica-Audio Azure, a great mastering EQ which can really deepen the sound stage, but also very useful on single instruments which have a broad frequency range.

Acustica-Audio Sand based on an older SSL hardware EQ, this EQ is simply amazing on drums, the low end is exactly what you want to hear on a kick drum and it’s a perfect EQ for shaping a snare sound.

Waves F6 dynamic EQ. Though I have several excellent dynamic EQs, I end up using this one a lot. It’s easy to use, and very versatile. I like the ability to change the attack and release, and the ability to work in Mid Side and change the EQ shape of any band. Importantly, it also sounds very transparent.

The other dynamic EQ I return again and again to is the McDSP AE400. I find the F6 easier to use, but when I can’t get what I need from that, the AE400 is the next one I go to. It sounds very transparent and reacts a little differently than the F6, which is why it’s a good companion dynamic EQ. It is also extremely versatile, offering control over attack, release and even ratio in addition to gain.

Specialist EQs

Kush Audio Clariphonic. A unique set of parallel high shelf EQs which are amazing on overheads and great for bringing out clarity in a transparent way on a variety of sources.

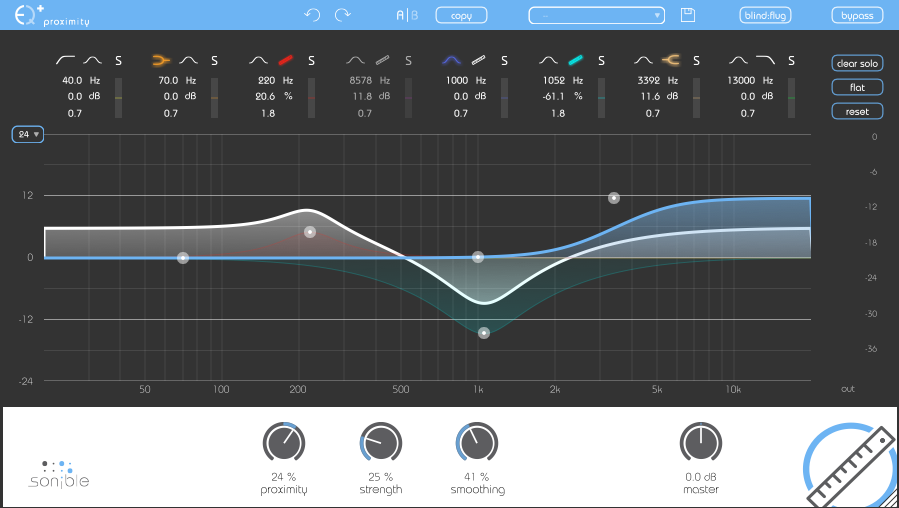

Sonible Proximity EQ. Another tool which makes use of the emense potentail of software. This EQ can reduce room ambience based on any EQ curve you set up. I’ve used this EQ to salvage recordings of live performances which would have otherwise been far too reverberant to use.

The Brainworx Plugin Alliance bx_panEQ allows you to control the panning of specific frequency areas of the audio. This can be a useful tool for fixing problems in a master were a remix is not possible (such as a live or historic recording) and can also be useful for sound design.

And there are so many more great EQs! These are just a handful which are either my goto EQs or EQs I felt deserved a special mention. I have many other EQs which I use regularly depending on the situation. Many of them have one thing which they do brilliantly. Others simply impart a special character that I need on certain projects.

I hope this article has given you some insight into the wonderful pallet of tonal shaping different EQs offer and some of the reasons they sound so different form one another.